Saw this the other day (find the link to the whole video after the gap)

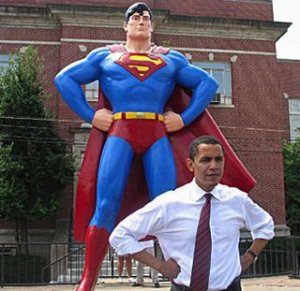

The best of the Obama-as-blank-screen readings — at once totally fascinating and symptomatic of a certain type of boomer leftist intellectual, the one driven to irrational exuberance over the contradiction between traditional origin myths and ‘radical breaks.’ The archetype Critchley summons to contain Obama is that of the empty postmodern hero, drained of all positive qualities, ‘open’ for being ultimately enigmatic, bearer of an essential mystery identified with his origin. Critchley invokes psychoanalysis to penetrate this mystery, using it to structure the more common fixations on the future president’s mixed race and international upbringing. Perhaps the most fascinating film versions of the postmodern man without qualities to come out of the ’70s (when his generation came into maturity) were aliens: the David Bowie character in Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) and Christopher Reeve’s Superman (1978). Both were updates of characters inherited from the ’50s — Klaatu and the George Reeves Superman. Subtracting the then-discredited rational paternalism magnified their strangeness, their aura of vulnerability and their capacity to reflect and transcend, through personal, moral suffering, the divisions of the Cold War society into which they had been thrust.

Right and left boomer critiques of Obama’s immense popularity tend to be carried out in the standard language of the belittling of Generation X, i.e. that his rhetoric is basically devoid of content, unoriginal, unpolitical, inauthentic, etc. This resistance partially stems from the fact that Obama defies readings based on identity or origin. Despite Critchley and others’ best efforts, not even the ambiguity of his racial politics can be fetishized in the usual way (as ‘oppositional,’ ‘transgressive,’ etc.), nor is he particularly convincing as a sex object, ‘alternative’ or otherwise. But he is also not, as Gen X heroes have tended to be (from the amoral ciphers of Bret Easton Ellis to Beavis and Butthead), aimless, apathetic, or nihilistic. What wins these critics over despite themselves, I think, is that as the first black president, Obama has actually realized the symbolic victory that American culture under Reagan and then the New World Order had dismissed as either impossible or irrelevant. He offers the opportunity to move on from battles over representation which a) seem to be all the American left has been capable of winning since the ’70s and b) seem to be carried out based on questionable assumptions about identity and identification that have nevertheless been protected from criticism due to their increasingly limited political utility. Obama’s election was not a victory over racial prejudice, but over an identity-based rhetoric of opposition. Though it’s been monopolized in mainstream politics by the Republicans, it has also been largely accepted by the Left as the only authentically political discourse. Reactions from this quarter have been accordingly ambivalent.

What sensible responses by people like Judith Butler(via) leave out, which exhort supporters to have their fun but be emotionally and practically ready for inevitable disappointment, is an analysis of how Obama’s rhetoric functions. They start from the assumption that his slogans are ’empty’ in the sense of being without content, and therefore not worth taking seriously. She is led to question her naive friends, but not the political assumptions she shares with them. It’s of course true that Obama relies on the same myths of ‘the American people,’ the overcoming of internal division, freedom, and inevitable sacrifice as just about every president before him. But, while the language of American presidential politics may not change, emphasis and strategic function do. So it’s important to understand these shifts, no matter how minute they may appear when written in books.

First we have to remember that every definition of ‘real’ Americans insists on their impatience with ideology and partisanship, a trait usually connected to good, honest work. Though the transcending of ideology despite/as intense nationalism is a feature of liberal ideology in general, what Habermas identified as “the Janus-face of the modern nation,” Americans seem especially invested in denying even its occasional suspension; any decline in the political capital of ‘natural unity’ always seems to coincide with a long and painful period of disillusionment. Recall that, despite their reputations, Bush and McCain both based their success on calls to unity: Bush’s “compassionate conservativism,” McCain’s “reaching across the aisle.” Indeed, they established their singularity precisely by touting consensus against partisanship — “uniter, not a divider” — another recurring feature of American political rhetoric. We find the distinctive qualities of American presidents in how they stage the reestablishment of continuity.

The following is from The Audacity of Hope, after Obama describes his ‘real America’ as those who “understand that politics today is a business and not a mission”:

“A government that truly represents these Americans — that truly serves these Americans — will require a different kind of politics. That politics will need to reflect our lives as they are actually lived. It won’t be prepackaged, ready to pull off the shelf. It will have to be constructed from the best of our traditions and will have to account for the darker aspect of our past. we will need to understand just how we got to this place, this land of warring factions and tribal hatreds. And we will need to remind ourselves, despite all our differences, just how much we share: common hopes, common dreams, a bond that will not break.”

Despite the mix of assertions and provisions, Obama defines consensus negatively: it is not autonomous from the everyday (“will need to reflect our lives”), not a commodity (“prepackaged”), not ahistorical or historical in a purely aesthetic way (i.e. quoting the Founding Fathers and celebrating WWII), not given (“constructed”). Our national scene, lacking consensus, is figured as premodern (full of “tribal hatreds”). In the last line, the naturalness of community is reasserted; the work necessary to construct it is also the work of remembering the eternally true. Of these themes, repeated again and again in Obama’s speeches, the attention to history is probably where he most distinguishes himself from Bush, most strikingly in his settling of accounts with the ’60s.

“I’ve always felt a curious relationship to the sixties,” he writes, and he singles out the basic contradiction of the Democratic Party since Carter defined it as the party of social values. The movements of the ’60s were for social values against the political-economic values of American imperialism, capitalism, chauvinism, and racism, and were only really coherent in that context. Their ‘values’ did not mix well with reconciliation, no matter how many of their activists eventually did. The usual response is repression. Part of what makes Obama so exciting is what his race forces a president to admit about the last 50 years of American life. In his speeches, he reconstructs the ’60s as an exciting era of struggles against injustice, and in the book locates himself as its “product.” His distance from the civil rights movement (his youth, his upbringing abroad, his white mother) leads him to seek a separation of its culture from its politics. He is not a product of its ideology, not a bearer of ‘black identity’ as constructed by and through Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, and their successors in the cultural sphere, but of the political struggles, defined in terms of their victories. In this way he subtly replaces the old ideology with a new one — his blackness is not a condmenation of America but its redemption, its ‘spirit’ authenticated in the fact of his election: “If there is anyone out there who still doubts that America is a place where all things are possible; who still wonders if the dream of our founders is alive in our time; who still questions the power of our democracy, tonight is your answer.”

There are two disciplines associated with the ’60s he rejects: economics and rhetoric. He is for a “dynamic free market” against the various radicals (including both Bush and environmentalists) and their oppositional, divisive politics even though he Feels Their Pain. Here is his reconciliation between right and left in the sphere of political economy, free market vs. social welfare:

“But our history should give us confidence that we don’t have to choose between an oppressive, government-run economy and a chaotic and unforgiving capitalism. It tells us that we can emerge from great economic upheavals stronger, not weaker. Like those who came before us, we should be asking ourselves what mix of policies will lead to a dynamic free market and widespread economic security, entrepreneurial innovation and upward mobility. And we can be guided throughout by Lincoln’s simple maxim: that we will do collectively, through our government, only those things that we cannot do as well or at all individually and privately.

In other words, we should be guided by what works.”

The various threads in this argument coalesce in his characterization of Reagan. Reagan’s aggressive foreign and domestic policies and his divisive rhetoric only worked for a tiny elite. But they did work. The ideological success of Reaganism was not just that it defended a certain position, still less that it made good on its populist promises (quite the opposite), but that it used what Obama identifies as the New Left’s rhetoric of intense partisanship to change the field of American political discourse against the left: “the more his critics carped, the more those critics played into the role he had written for them — a band of out-of-touch, tax-and-spend, blame-America-first, politically correct elites.” It’s not difficult to see in retrospect that the rewriting of political language and the marginalization in advance of his opponents has always been key to Obama’s strategy.

Idealized pragmatism allows the establishment of formal equivalence between right and left radicals, rejecting them together as “cynical.” Their real differences are politely bracketed — the Iraq war and the financial crisis join the collapse of communism as undeniable proofs of failed, impractical ideologies. The (obviously flawed) existing popular language with which to debate “socialism” vs. “capitalism,” or “free market” vs. “social welfare” has been swept aside, but their defenders are redeemed by shared American values, welcomed back into the fold. In this transitional period at least, when Obama’s policies are still unclear, his success in reframing American politics in strictly idealist terms — “idealism” against “cynicism” — is undeniable. His ability to turn the Iraq war and the finance crisis in his favor has closed off any attempt to analyze him in terms of existing theory; we critics are virtually locked into waiting patiently for the results.

We are now finally able to get at the truly unique aspect of Obama’s politics. Almost no one seems to recognize that he has already anticipated the most common criticism of him, that his rhetoric and even his person are ’empty’ and meaningless. The point of his slogans is not just that they remain open to different meanings, in the typical fashion of traditional advertising. They are open to different uses; they open outward, as a call to fill an empty signifier with concrete action (like contemporary advertising). Reid Kotlas of Planomenology is one of the few to get it right: “The republican criticism that Obama talks a lot about change, but doesn’t tell us what exactly this change is, is thus poorly aimed: it is by virtue of leaving the goal of this change open, by entrusting us with its realization, that Obama’s message is truly effective.” Critchley remains focused on the out-of-context “blank screen” quote. Also his “listlessness” which “generates in us a desire to love him,” but in a “restrained,” liberal sort of way. I think Grant Park proves this reading is at least incomplete. Obamamania was always just as fervent as Palin-mania, just without the threat of violence. Critchley’s psychoanalytic reading acknowledges the political valence of the ethical demand Obama makes on his supporters, restaging boring liberal compromise as potentially radical. “No one is exempt from the call to find common ground,” Obama asserts; to substitute mere words for action is “to relinquish our best selves.” But he pointedly declines to critique it. Critique, however, is necessary to understand that Obama’s rhetoric is directed at organizing, not just generating fantasy fodder.

His opacity, his refusal, we might say, to entirely identify with himself, instead offering his biography and campaign together as a kind of open-source “vehicle” for emotional and practical investment, is his most important political move. As Critchley does note, the prophetic plays a big role here. “Change we can believe in” is pure speculation, open to further speculation. If we have (as the pessimists say) been witnessing the steady deterioration of political discourse over the past however many years, then this would have to be its absolute nadir. And yet at the same time it spawned a massive popular mobilization. What Butler has to say about left disavowal should also be applied to Obama himself, with the proviso that his provoked the movement that got him elected while ours produced it: beyond liberalism’s politics of anti-politics, Obama, by visibly taking a step back from his own power, has inspired the masses to create their own anti-politics under his brand. His election is not his victory, it’s our victory — his win has nothing to do with his race, but our enlightened attitude toward race — he’s done everything shy of announcing that his office will not be in his power but in our power. We are not led to identify with him. We are led to identify our politics through him.

This is not to say that his supporters do not think, only that the campaign is (pragmatically) indifferent to any thoughts they might have which can’t be incorporated into the ‘movement.’

Doesn’t all the increasingly anxious speculation about Obama (this post included) have something to do with the fear that when he actually becomes president, something precious will have been lost? We already have intimations that this will be the case, though it’s impossible to tell exactly how the actual dynamics of his relationship with his activists will play out. Just as ironic distance fails to negate its real investments, the image of Change fails to negate its material function as an image, a commodity bought and paid for by Wall Street with the American people as (now) minority shareholders. If the image America just opted into is that of Future President Obama giving our politics back to us, then the Left, if there is still to be one apart from Team Change, has to ask itself: would this obviously compromised image be so appealing if the practical (anti-) politics it enabled were not ten times more radical than the most radical of ideologies?